Lesson 9 - Quality Teaching in a Digital Age

2. What Do We Mean by Quality When Teaching in a Digital Age?

2.1. Definitions

Probably there is no other topic in education which generates so much discussion and controversy as ‘quality’. Many books have been written on the topic, but I will cut to the chase and give my definition of quality up-front. For the purposes of this book, quality is defined as:

Teaching methods that successfully help learners develop the knowledge and skills they will require in a digital age.

This, of course, is my short answer to the question of what quality is. A longer answer means looking, at least briefly, at:

- Institutional and degree accreditation

- Internal (academic) quality assurance processes

- Differences in quality assurance between traditional classroom teaching and online and distance education

- The relationship between quality assurance processes and learning outcomes

- ‘Quality assurance fit for purpose’: meeting the goals of education in a digital age

This will then provide the foundations for my recommendations for quality teaching that will follow in this lesson.

Most governments act to protect consumers in the education market by ensuring that institutions are properly accredited and the qualifications they award are valid and are recognized as being of ‘quality.’ However, the manner in which institutions and degrees are accredited varies a great deal. The main difference is between the USA and virtually any other country.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Network for Education Information states in its description of accreditation and quality assurance in the USA:

Accreditation is the process used in U.S. education to ensure that schools, postsecondary institutions and other education providers meet, and maintain, minimum standards of quality and integrity regarding academics, administration, and related services. It is a voluntary process based on the principle of academic self-governance. Schools, postsecondary institutions and programs (faculties) within institutions participate in accreditation. The entities which conduct accreditation are associations comprised of institutions and academic specialists in specific subjects, who establish and enforce standards of membership and procedures for conducting the accreditation process.

Both the federal and state governments recognize accreditation as the mechanism by which institutional and programmatic legitimacy are ensured. In international terms, accreditation by a recognized accrediting authority is accepted as the U.S. equivalent of other countries’ ministerial recognition of institutions belonging to national education systems.

In other words, in the USA, accreditation and quality assurance is effectively self-regulated by the educational institutions through their control of accreditation agencies, although the government does have some ‘weapons of enforcement’, mainly through the withdrawal of student financial aid for students at any institution that the U.S. Department of Education deems to be failing to meet standards.

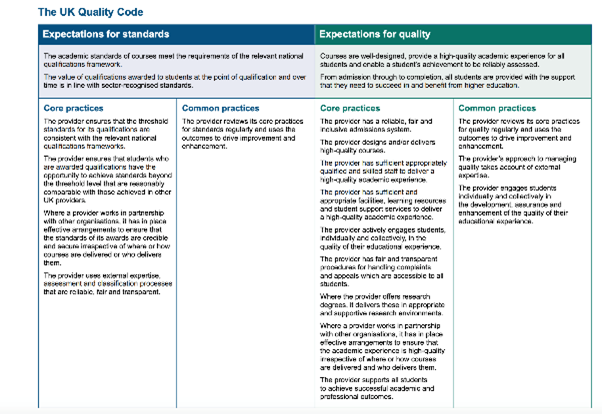

In many other countries, government has the ultimate authority to accredit institutions and approve degrees, although in countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom, this too is often exercised by arm’s length agencies appointed by the government, but consisting mainly of representatives from the various institutions within the system. These bodies have a variety of names, but Degree Quality Assurance Board is a typical title. However, in recent years, some regulatory agencies such as the United Kingdom’s Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education has adopted formal quality assurance processes based on practices that originated in the industry. The U.K. QAA’s revised Quality Code for Higher Education is set out below:

However, although hardly contentious, such system-wide codes are too general for the specifics of ensuring quality in a particular course. Many institutions as a result of pressure from external agencies have therefore put in place formal quality assurance processes over and beyond the normal academic approval processes (see Clarke-Okah and Daniel, 2010, for a typical, low-cost example).