Lesson 9 - Quality Teaching in a Digital Age

| Site: | Technology-Enabled Learning Lounge |

| Course: | Teaching in a Digital Age |

| Book: | Lesson 9 - Quality Teaching in a Digital Age |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 28 January 2026, 7:20 PM |

Table of contents

- 1. Watch this Video on Quality Teaching in a Digital Age

- 2. What Do We Mean by Quality When Teaching in a Digital Age?

- 3. Nine Steps to Quality Teaching in a Digital Age

- 4. Step One: Decide How You Want to Teach

- 5. Step Two: What Kind of Course or Program?

- 6. Step Three: Work in a Team

- 7. Step Four: Build on Existing Resources

- 8. Step Five: Master the Technology

- 9. Step Six: Set Appropriate Learning Goals

- 10. Step Seven: Design Course Structure and Learning Activities

- 10.1. Some General Observations About Structure in Teaching

- 10.2. Institutional Organizational Requirements of Face-to-Face Teaching

- 10.3. Institutional Organizational Requirements of Online Teaching

- 10.4. How Much Work is an Online Course?

- 10.5. Strong or Loose Structure?

- 10.6. Moving a Face-to-Face Course Online

- 10.7. Structuring a Blended Learning Course

- 10.8. Designing a New Online Course or Program

- 10.9. Key Principles in Structuring a Course

- 10.10. Designing Student Activities

- 10.11. Many Structures, One High Standard

- 11. Step Eight: Communicate, Communicate, Communicate

- 11.1. The Concept of ‘Instructor Presence’

- 11.2. Instructor Presence and the Loneliness of the Long-Distance Learner

- 11.3. Setting Students’ Expectations

- 11.4. Teaching Philosophy and Online Communication

- 11.5. Choice of Medium for Instructor Communication

- 11.6. Managing Online Discussion

- 11.7. Cultural and Other Student Differences

- 12. Step Nine: Evaluate and Innovate

- 13. Building a Strong Foundation of Course Design

- 14. Activity (Reflective Thinking, Note Taking and Discussion)

- 15. Key Takeaways

1. Watch this Video on Quality Teaching in a Digital Age

2. What Do We Mean by Quality When Teaching in a Digital Age?

If you have followed the journey through all the previous lessons of this book, you will have been subject to a great deal of information: philosophical, empirical, technological, and administrative, set within a framework of issues related to the needs of learners in a digital age. It is now time to pull all this together into a pragmatic set of action steps that will enable you to apply these ideas and concepts within the everyday circumstances of teaching.

Thus, the aim of this lesson is to provide some practical guidelines for teachers and instructors to ensure quality teaching in a digital age. This will mean drawing on all the previous lessons in this book, so there will inevitably be some repetition in this lesson of the content of earlier chapters. Their aim here is to pull it all together towards developing quality digitally based courses and programs fit for a digital age.

Before I do this, however, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by ‘quality’ in teaching and learning, because I am using ‘quality’ here in a very specific way.

2.1. Definitions

Probably there is no other topic in education which generates so much discussion and controversy as ‘quality’. Many books have been written on the topic, but I will cut to the chase and give my definition of quality up-front. For the purposes of this book, quality is defined as:

Teaching methods that successfully help learners develop the knowledge and skills they will require in a digital age.

This, of course, is my short answer to the question of what quality is. A longer answer means looking, at least briefly, at:

- Institutional and degree accreditation

- Internal (academic) quality assurance processes

- Differences in quality assurance between traditional classroom teaching and online and distance education

- The relationship between quality assurance processes and learning outcomes

- ‘Quality assurance fit for purpose’: meeting the goals of education in a digital age

This will then provide the foundations for my recommendations for quality teaching that will follow in this lesson.

Most governments act to protect consumers in the education market by ensuring that institutions are properly accredited and the qualifications they award are valid and are recognized as being of ‘quality.’ However, the manner in which institutions and degrees are accredited varies a great deal. The main difference is between the USA and virtually any other country.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Network for Education Information states in its description of accreditation and quality assurance in the USA:

Accreditation is the process used in U.S. education to ensure that schools, postsecondary institutions and other education providers meet, and maintain, minimum standards of quality and integrity regarding academics, administration, and related services. It is a voluntary process based on the principle of academic self-governance. Schools, postsecondary institutions and programs (faculties) within institutions participate in accreditation. The entities which conduct accreditation are associations comprised of institutions and academic specialists in specific subjects, who establish and enforce standards of membership and procedures for conducting the accreditation process.

Both the federal and state governments recognize accreditation as the mechanism by which institutional and programmatic legitimacy are ensured. In international terms, accreditation by a recognized accrediting authority is accepted as the U.S. equivalent of other countries’ ministerial recognition of institutions belonging to national education systems.

In other words, in the USA, accreditation and quality assurance is effectively self-regulated by the educational institutions through their control of accreditation agencies, although the government does have some ‘weapons of enforcement’, mainly through the withdrawal of student financial aid for students at any institution that the U.S. Department of Education deems to be failing to meet standards.

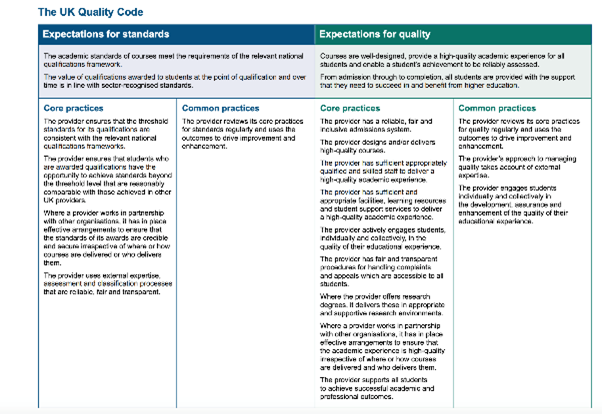

In many other countries, government has the ultimate authority to accredit institutions and approve degrees, although in countries such as Canada and the United Kingdom, this too is often exercised by arm’s length agencies appointed by the government, but consisting mainly of representatives from the various institutions within the system. These bodies have a variety of names, but Degree Quality Assurance Board is a typical title. However, in recent years, some regulatory agencies such as the United Kingdom’s Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education has adopted formal quality assurance processes based on practices that originated in the industry. The U.K. QAA’s revised Quality Code for Higher Education is set out below:

However, although hardly contentious, such system-wide codes are too general for the specifics of ensuring quality in a particular course. Many institutions as a result of pressure from external agencies have therefore put in place formal quality assurance processes over and beyond the normal academic approval processes (see Clarke-Okah and Daniel, 2010, for a typical, low-cost example).

2.2. Internal Quality Assurance

It can be seen then that the internal processes for ensuring quality programs within an institution are particularly important. Although again the process can vary considerably between institutions, at least in universities, the process is fairly standard.

Assuring the Quality of a ProgramA proposal for a new degree will usually originate from a group of faculty/instructors within a department. The proposal will be discussed and amended at departmental and/or Faculty meetings, then once approved will go to the university senate for final approval. The administration in the form of the Provost’s Office will usually be involved, particularly where resources, such as new appointments, are required.

Although this is probably an over-generalization, significantly the proposal will contain information about who will teach the course and their qualifications to teach it, the content to be covered within the program (often as a list of courses with short descriptions), a set of required readings, and usually something about how students will be assessed. Increasingly, such proposals may also include broad learning outcomes for the program.

If there is a proposal for courses within a program or the whole program to be delivered fully online, it is likely that the proposal will come under greater internal scrutiny. What is unlikely to be included in a proposal though is what methods of teaching will be used. This is usually considered the responsibility of individual faculty members or the individual teacher (unless you are an adjunct or contract instructor). It is this aspect of quality – the effectiveness of the teaching method or learning environment for developing the knowledge and skills in a digital age – with which this lesson is concerned.

Assuring the Quality of Classroom TeachingThere are many guidelines for quality traditional classroom teaching. Perhaps the most well known are those of Chickering and Gamson (1987), based on an analysis of 50 years of research into best practices in teaching. They argue that good practice in undergraduate education:

- Encourages contact between students and faculty.

- Develops reciprocity and cooperation among students.

- Encourages active learning.

- Gives prompt feedback.

- Emphasizes time on task.

- Communicates high expectations.

- Respects diverse talents and ways of learning.

However, these standards should apply equally to both face-to-face and online teaching.

Quality in Online Courses and ProgramsBecause online learning was new and hence open to concern about its quality, there have also been many guidelines, best practices, and quality assurance criteria created and applied to online programming. All these guidelines and procedures have been derived from the experience of previously successful online programs, best practices in teaching and learning, and research and evaluation of online teaching and learning. A comprehensive list of online quality assurance standards, organizations, and research on online learning.

Jung and Latchem (2012), in a review of quality assessment processes in a large number of online and distance education institutions around the world, make the following important points about quality assurance processes for online and distance education within institutions:

Focus on outcomes as the leading measure of quality

Take a systemic approach to quality assurance

See QA as a process of continuous improvement

Move the institution from external controls to an internal culture of quality

Poor quality has very high costs so investment in quality is worthwhile

Ensuring quality in online learning is not rocket science. There is no need to build a bureaucracy around this, but there does need to be some mechanism, some way of monitoring instructors or institutions when they fail to meet these standards. However, we should also do the same for campus-based teaching. As more and more already accredited (and ‘high quality’) campus-based institutions start moving into hybrid learning, the establishment of quality in the online learning elements of programs will become even more important.

2.3. Consistency in Applying Quality Standards

There are plenty of evidence-based guidelines for ensuring quality in teaching, both face-to-face and online. The main challenge then is to ensure that teachers and instructors are aware of these best practices and that institutions have processes in place to ensure that guidelines for quality teaching are implemented and followed.

Quality assurance methods are valuable for agencies concerned about rogue private providers, or institutions using online learning to cut corners or reduce costs without maintaining standards (for instance, by hiring untrained adjuncts, and giving them an unacceptably high teacher-student ratio to manage). QA methods can be useful for providing instructors new to teaching with technology, or struggling with its use, with models of best practice to follow. But for any reputable state university or college, the same quality assurance standards should apply equally to face-to-face and online teaching, even if slightly adjusted for the difference in the delivery method.

2.4. Quality Assurance, Innovation and Learning Outcomes

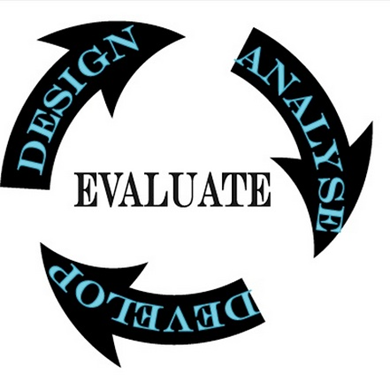

Most QA processes are front-loaded, in that they focus on inputs – such as the academic qualifications of faculty, or the processes to be adopted for effective teachings, such as clear learning objectives, or systems-based course design methods, such as ADDIE – rather than outputs, such as what students have actually learned. QA processes also tend to be backward-looking, that is, they focus on past best practices.

This needs to be considered especially when evaluating new teaching approaches. Butcher and Hoosen (2014) state:

The quality assurance of post-traditional higher education is not straightforward, because openness and flexibility are primary characteristics of these new approaches, whereas traditional approaches to quality assurance were designed for teaching and learning within more tightly structured frameworks.

However, Butcher and Hoosen (2014) go on to say that:

Fundamental judgments about quality should not depend on whether education is provided in a traditional or post-traditional manner …the growth of openness is unlikely to demand major changes to quality assurance practices in institutions. The principles of good quality higher education have not changed…. Quality distance education is a sub-set of quality education…Distance education should be subject to the same quality assurance mechanisms as education generally.

Such arguments though offer a particular challenge for teaching in a digital age, where learning outcomes need to include the development of skills such as independent learning, facility in using social media for communication, and knowledge management, skills that have often not been explicitly identified in the past. Quality assurance processes are not usually tied to specific types of learning outcomes but are more closely linked to general performance measures such as course completion rates, time to degree completion, or grades based on past learning goals.

Furthermore, new media and new methods of teaching are emerging that have not been around long enough to be subject to analysis of best practices. A too rigid view of quality assessment based on past practices could have serious negative implications for innovation in teaching and for meeting newly emerging learning needs. ‘Best practice’ may need occasionally to be challenged, so new approaches can be experimented with and evaluated.

2.5. Getting to the Essence of Quality

Institutional accreditation, internal procedures for program approval and review, and formal quality assurance processes, while important, particularly for external accountability, do not really get to the heart of what quality is in teaching and learning. They are rather like the pomp and circumstance of state occasions. The changing of the guard in front of the palace is ceremonial, rather than a practical defence against revolution, invasion, or a terrorist attack on the President or the monarchy. As important as ceremonies and rituals are to national identity, a strong state is bound by deeper ties. Similarly, an effective school, college, or university is much more than the administrative processes that regulate teaching and learning.

At its worst, quality management can end up with many boxes on a questionnaire being ticked, in that the management processes are all in place, without in fact investigating whether students are really learning more or better as a result of using technology. In essence, teaching and learning are very human activities, often requiring for success a strong bond between teacher and learner. There is a powerful affective or motivational aspect of learning, which a ‘good’ teacher can tap into and steer.

One reason for the concern of many teachers and instructors about using technology for teaching is that it will be difficult or even impossible to develop that emotional bond that helps see a learner through difficulties or inspires someone to greater heights of understanding or passion for the subject. However, technology is now flexible and powerful enough, when properly managed, to enable such bonds to be developed, not only between teacher and learner but also between learners themselves, even though they may never meet in person.

Thus, any discussion of quality in education needs to recognize and accommodate these affective or emotional aspects of learning. This is a factor that is too often ignored in behaviourist approaches to the use of technology or to quality assurance. Consequently, in what follows in this lesson, as well as incorporating best practices in technical terms, the more human aspects of teaching and learning are considered, even or especially within technology-based learning environments.

2.6. Quality Assurance: Fit for Purpose in a Digital Age

At the end of the day, the best guarantees of quality in teaching and learning fit for a digital age are:

- Well-qualified subject experts also well trained in both teaching methods and the use of technology for teaching

- Highly qualified and professional learning technology support staff

- Adequate resources, including appropriate teacher/student ratios

- Appropriate methods of working (teamwork, project management)

- Systematic evaluation leading to continuous improvement

Much more attention needs to be directed at what campus-based institutions are doing when they move to hybrid or online learning. Are they following best practices, or even better, developing innovative, better teaching methods that exploit the strengths of both classroom and online learning? The design of xMOOCs and the high drop-out rates in the USA of many two year colleges new to online learning suggest they are not.

If the goal or purpose is to develop the knowledge and skills that learners will need in a digital age, then this is the ‘standard’ by which quality should be assessed, while at the same time taking into account what we already know about general best practices in teaching. The recommendations for quality teaching in a digital age that follow in this lesson are based on this key principle of ‘fit for purpose.

3. Nine Steps to Quality Teaching in a Digital Age

In the previous section, I pointed out that there are lots of excellent quality assurance standards, organizations and research available online, and I’m not going to duplicate these. Instead, I’m going to suggest a series of practical steps towards implementing such standards.

3.1. An Alternative to Using the ADDIE Model to Assure Quality

I am assuming that all the standard institutional processes towards program approval have been taken, although it is worth pointing out that it might be worth thinking through my nine steps outlined below before finally submitting a proposal for a new blended or online course or program. My nine steps approach would also work when considering the redesign of an existing course.

The ‘standard’ quality practice for developing a fully online course would be to develop a systems approach to design through something like the ADDIE model. Puzziferro and Shelton (2008) provide an excellent example.

However, I have already pointed to some of the limitations of a systems approach in the volatile, uncertain, chaotic, and ambiguous digital age, and in any case, I think we need a process that works not only for fully online courses but also for face-to-face, blended and hybrid courses and programs. So I am aiming for a more flexible but still a systematic approach to quality course design, but broad enough to include a wide range of delivery methods. To get a sense of the difference in my approach to a ‘standard’ systems model, the ADDIE model wouldn’t kick in until around Step 6 below.

Furthermore, it is not enough just to look at the actual teaching of the course, but also at building a complete learning environment in which the learning will take place. So, to provide a quality framework, I will outline nine steps, although they are more likely to be developed in parallel than sequentially. Nevertheless, there is a logic to the order.

- Step 1: Decide how you want to teach

- Step 2: Decide on the mode of delivery

- Step 3: Work in a Team

- Step 4: Build on existing resources

- Step 5: Master the technology

- Step 6: Set appropriate learning goals

- Step 7: Design course structure and learning activities

- Step 8: Communicate, communicate, communicate

- Step 9: Evaluate and innovate

These steps will draw on material from earlier in this book. Indeed, if you have been doing the activities thoroughly, you may already be able to answer the questions raised as you work through each of the nine steps.

4. Step One: Decide How You Want to Teach

Of all the nine steps, this is the most important, and, for most instructors, the most challenging, as it may mean changing long-established patterns of behaviour.

4.1. How Would I Really Like to Teach This Course?

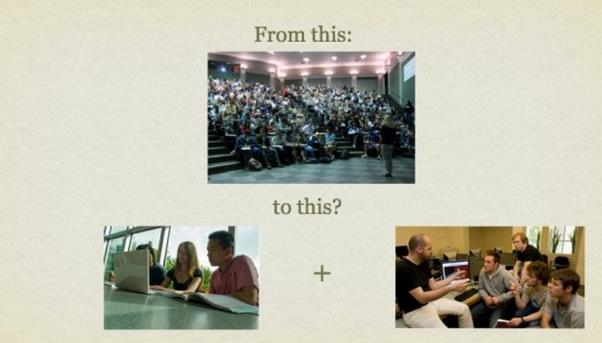

This question asks you to consider your basic teaching philosophy. What is my role as an instructor? Do I take an objectivist view, that knowledge is finite and defined, that I am an expert in the subject matter who knows more than the students, and thus my job is to ensure that I transfer as effectively as possible that information or knowledge to the student? Or do I see learning as individual development where my role is to help learners to acquire the ability to question, analyse and apply information or knowledge?

Do I see myself more as a guide or facilitator of learning for students? Or maybe you would like to teach in the latter way, but you are faced in classroom teaching with a class of 200 students which forces you to fall back on a more didactic form of teaching. Or maybe you would like to combine both approaches but can’t because of the restrictions of timetables and curriculum.

4.2. What’s Wrong with the Way I’m Teaching at the Moment?

Another place to start would be by thinking about what you don’t like about the current course(s) you are teaching. Is there too much content to be covered? Could you deal with this in another way, perhaps by getting students to find, analyse and apply content to solve problems or do research? Could you focus more on skills in this context? If so, how could you provide appropriate activities to enable students to practice these skills? How much of this could they do on their own, so you can manage your workload better?

Are the students too diverse, in that some students really struggle while others are impatient to move ahead? How could I make the teaching more personalised, so that students at all levels of ability could succeed in this course? Could I organise my teaching so that students who struggle can spend more time on task, or those that are racing ahead have more advanced work to do?

Or perhaps you are not getting enough discussion or critical thinking because the class is too large. Could you use technology and re-organise the class differently to get students studying in small groups, but in such a way you can monitor and guide the discussions? Can you break the work up into chunks that the students should be able to do on their own, such as mastering the content, so you can focus on discussion and critical thinking with students when they come to class?

For instance, by moving a great deal of the content online, maybe you can free up more time for interaction with students, in large or smaller groups, either in class or online, and at the same time reduce the number of lectures to large classes. Some instructors have redesigned large lecture classes of 200 students, by breaking down the class into 10 groups, moving much of the lecture material online, and then the instructor spends at least one week with each of the 10 groups in online discussion, interaction and group activities, thus getting more interaction with all the students.

In another context, do you feel restricted by the limitations of what can be done in labs or workshops, because of the time it takes to set up experiments or equipment, or because students don’t really have enough hands-on time? Could I re-organise the teaching so that students do a lot of preparation online, so they can concentrate in the lab or workshop on what they have to do by hand. Could they report on their lab or workshop experiences afterwards, online, through an e-portfolio, for instance? Can I find good open educational resources, such as video or simulations, that would reduce the need for lab time? Or could I create good quality demonstration videos, so I can spend more time talking with students about the implications?

Finally, are you just overloaded with work on this course, because there are too many student questions to be answered, or too many assignments to mark? How could you re-organise the course to manage your workload more easily? Could students do more by working together and helping each other? if so, how would you create groups that might meet this goal? Could you change the nature of the assignments so that students do more project work, and slowly build e-portfolios of their work during the course so you can more easily monitor their progress, while at the same time building up an assessment of their learning?

4.3. Use Technology to Re-think Your Teaching

Considering using new technologies or an alternative delivery method will give you an opportunity to rethink your teaching, perhaps to be able to tackle some of the limitations of classroom teaching, and to renew your approach to teaching. One way to help you rethink how you want to teach is to think of how you could build a rich learning environment for the course.

Using technology or moving part or all of your course online opens up a range of possibilities for teaching that may not be possible in the confines of a scheduled three credit weekly semester of lectures. It may mean not doing everything online but focusing the campus experience on what can only be done on campus. Alternatively, it may enable you to totally rethink the curriculum, to exploit some of the benefits of online learning, such as getting students to find, analyse and apply information for themselves.

Thus if you are thinking about a new course, or redesigning one that you are not too happy with, take the opportunity before you start teaching the course or program to think about how you’d really like to be teaching, and whether this can be accommodated in a different learning environment. It’s not a decision you have to make immediately though. As you work through the nine steps, it will become easier to make this decision. The important point is to be open to doing things differently.

4.4. What Not to Do

However, you can be sure of one thing. If you merely put your lecture notes up on the web, or record your 50-minute lectures for downloading, then you are almost certain to have lower student completion rates and poorer grades than for your face-to-face class. I make this point because it is tempting for face-to-face instructors merely to move their method of classroom teaching online, such as using lecture capture for students to download recorded classroom lectures at home or using web conferencing to deliver live lectures over the internet. However there is much evidence to suggest that doing this does not lead to good results (see for instance, Figlio, Rush and Yin, 2010).

The problem with just moving lectures online is that it fails to take account of a key requirement for most online learners: flexibility. When students are studying online, their needs are different from when they are in class. Restricted ‘office hours’ when the instructor is available for students do not provide the flexibility of contact that students need when working online. Students tend to work in smaller chunks of time when studying online, in several short bursts, and rarely more than an hour without a break. Online work then needs to be broken up into manageable ‘chunks.’ A synchronous web cast may be scheduled at times when online students are working. More importantly, online learning allows us to deliver content or information in ways that lead to better learning than through a one-hour lecture.

Thus, it is important to design teaching in such a way that it best suits the different modes of learning that students will use. Fortunately, there has been a lot of experience and research that have identified the key design principles for both classroom and online teaching. This is what the next eight steps are about.

4.5. A Chance to Fly

Technologies and new modes of delivery open up wonderful opportunities to rethink completely the teaching process. Teachers and instructors with deep knowledge of their subject can now find many unique and exciting ways to open up their teaching and to integrate their research into their teaching. The main restriction now is not time nor money, but lack of imagination. Those with the imagination will be able to fly into previously unthinkable ways of teaching their subject.

5. Step Two: What Kind of Course or Program?

5.1. Choosing Mode of Delivery

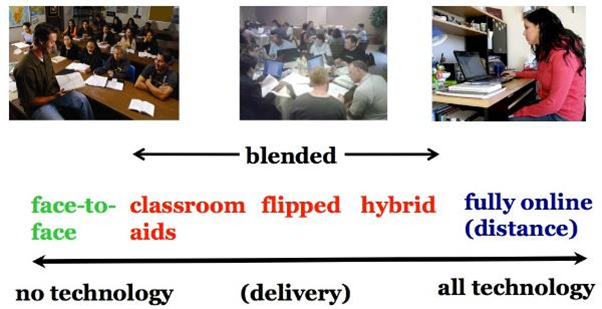

Determining what kind of course in terms of the mix of face-to-face and online teaching is the natural next step after considering how you want to teach a course. This topic has been dealt with extensively in , so to summarise, there are four factors or variables to take into account when deciding what ‘mix’ of face-to-face and online learning will be best for your course:

- Your preferred teaching philosophy – how you like to teach (see Step 1)

- The needs of the students (or potential students)

- The demands of the discipline

- The resources available to you

Although an analysis of all the factors is an essential set of steps to take in making this decision, in the end it will come down to a mainly intuitive decision, taking into account all the factors. This becomes particularly important when looking at a program as a whole.

5.2. Who Should Make the Decision?

While individual instructors should be heavily involved in deciding the best mix of online and face-to-face teaching in their specific course, it is worth thinking about this on a program rather than an individual course basis. For instance, if we see the development of independent learning skills as a key program outcome, then it might make sense to start in the first year with mainly face-to-face classes, but gradually over the length of the program introduce students to more and more online learning, so that the end of a four year degree they are able and willing to take some of their courses fully online.

Certainly every program should have a mechanism for deciding not only the content and skills or the curriculum to be covered in a program, but also how the program will be delivered, and hence the balance or mix of online and face-to-face teaching throughout the program. This should become integrated into an annual academic planning process that looks at both methods of teaching as well as content to be covered in the program (see Bates and Sangrà, 2011).

6. Step Three: Work in a Team

One of the strongest means of ensuring quality is to work as a team.

6.1. Why Work in a Team?

For many teachers and instructors, classroom teaching is an individual, largely private activity between the instructor and students. Teaching is a very personal affair. However, blended and especially fully online learning are different from classroom teaching. They require a range of skills that most teachers and instructors, and particularly those new to online teaching, are unlikely to have, at a least in a developed, ready-to-use form.

The way an instructor interacts online has to be organized differently from in class, and particular attention has to be paid to providing appropriate online activities for students, and to structuring content in ways that facilitate learning in an asynchronous online environment. Good course design is essential to achieve quality in terms of developing the knowledge and skills needed in a digital age. These are pedagogical issues, in which most post-secondary instructors have had little training. In addition, there are also technology issues. Novice teachers and instructors are likely to need help in developing graphics or video materials, for example.

Another reason to work in a team is to manage workload. There is a range of technological activities that are not normally required of classroom teachers and instructors. Just managing the technology will be extra work if instructors do it all themselves. Also, if the online component of a course is not well designed or integrated with the face-to-face component, if students are not clear what they should do, or if the material is presented in ways that are difficult to understand, the teacher or instructor will be overwhelmed with student e-mail. Instructional designers, who work across different courses, and who have training in both course design and technology, can be an invaluable resource for novices teaching online for the first time.

Thirdly working with colleagues in the same department who are more experienced in online learning can be a very good means to get quickly to a high-quality online standard, and again can save time. For instance, in one university I worked in, three faculty members in the same department were developing different courses with online components. However, these courses often needed graphics of the same equipment discussed in all three courses. The three instructors got together and worked with a graphic designer to create high quality graphics that were shared between all three instructors. This also resulted in discussions about overlap and how best to make sure there was better integration and consistency between the three courses. They could do this with their online courses more easily than with the classroom courses, because the online course materials can be more easily shared and observed.

Lastly, especially where large lecture classes are being re-designed, there may be a cohort of teaching assistants that may need to be trained, organised and managed. In some institutions, part-time adjunct faculty will also need to be involved. This means clarifying roles for the senior faculty member, the adjunct or contract faculty, the teaching assistants, and the learning technology support staff.

For many teachers and instructors, developing teaching in a team is a big cultural shift. However, the benefits of doing this for online or blended learning are well worth the effort. As teachers and instructors become more experienced in blended and online learning, there is less need for the help of an instructional designer, but many experienced instructors now prefer to continue working in a team, because it makes life so much easier for them.

6.2. Who is in the Team?

This will depend to some extent on the size of the course. In most cases, for a blended or online course with one main faculty member or subject expert, and a manageable number of students, the instructor will normally work with an instructional designer, who in turn can call on more specialist staff, such as a web or graphic designer or a media producer, as needed.

If however it is a course with many students and several instructors, adjunct faculty and/or teaching assistants, then they should all work together as a team, with the instructional designer. Also in some institutions a librarian is an important member of the team, helping identify resources, dealing with copyright issues and ensuring that the library is able to respond to learners’ needs when the course is being offered.

6.3. What About Academic Freedom? Do I Lose it Working in a Team?

No. The instructor(s) will always have final say over content and how it is to be taught. Instructional designers are advisers but responsibility for the content of the course, the way it is taught, and assessment methods always remains with the faculty member.

However, instructional and media producers should not be treated as servants, but as professionals with specialized skills. They should be respected and listened to. Often the instructional designer will have more experience of what will work and what will not in blended or online learning. Surgeons work with anaesthetists and nurses and trust them to do their jobs properly. The working relationship between instructors and instructional designers and media producers should be similar.

Working in a team makes life a lot easier for instructors when teaching blended or online courses. Good course design, which is the area of expertise of the instructional designer, not only enables students to learn better but also controls faculty workload. Courses look better with good graphic and web design and professional video production. Specialist technical help frees up instructors to concentrate on teaching and learning. What’s not to like?

This of course will depend heavily on the institution providing such support through a centre of teaching and learning. Nevertheless, this is an important decision that needs to be implemented before course design begins.

7. Step Four: Build on Existing Resources

The importance of using existing resources have been stressed in several parts of the book.

7.1. Moving Content Online

Time management for teachers and instructors is critical. A great deal of time can be spent converting classroom material into a form that will work in an online environment, but this can really increase workload. For instance, PowerPoint slides without a commentary often either miss the critical content or fail to cover nuances and emphasis. This may mean either using lecture capture to record the lecture or having to add a recorded commentary over the slides at a later date. Transferring lecture notes into pdf files and loading them up into a learning management system is also time consuming. However, this is not the best way to develop online materials, both for time management and pedagogical reasons.

In Step 1 I recommended rethinking teaching, not just moving recorded lectures or class PowerPoint slides online but developing materials in ways that enable students to learn better. Now in Step 4 I appear to be contradicting that by suggesting that you should use existing resources. However, the distinction here is between using existing resources that do not transfer well to an online learning environment (such as a 50-minute recorded lecture) and using materials already specifically developed or suitable for learning in an online environment.

7.2. Use Existing Online Content

The Internet, and in particular the World Wide Web, has an immense amount of content already available, and this was discussed extensively. Much of it is freely available for educational use, under certain conditions (e.g. acknowledgement of the source – look for the Creative Commons license usually at the end of the web page). You will find such existing content varies enormously in quality and range. Top universities such as MIT, Stanford, Princeton and Yale have made available recordings of their classroom lectures, etc., while distance teaching organizations such as the UK Open University have made all their online teaching materials available for free use. Much of this can be found at these sites:

- OpenCourseWare (MIT)

- iTunesU

- OpenLearn (U.K. Open University)

- The Open Education Consortium (courses in STEM: science, technology, engineering, math)

- Open Learning Initiative (Carnegie Mellon)

- MERLOT

However, there are now many other sites from prestigious universities offering open course ware. (A Google search using ‘open educational resources’ or’ OER’ will identify most of them.)

In the case of the prestigious universities, you can be sure about the quality of the content – it’s usually what the on-campus students get – but it often lacks the quality needed in terms of instructional design or suitability for online learning (for more discussion on this see Hampson (2015); or OERs: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly). Open resources from institutions such as the UK Open University or Carnegie Mellon’s Open Learn Initiative usually combine quality content with good instructional design.

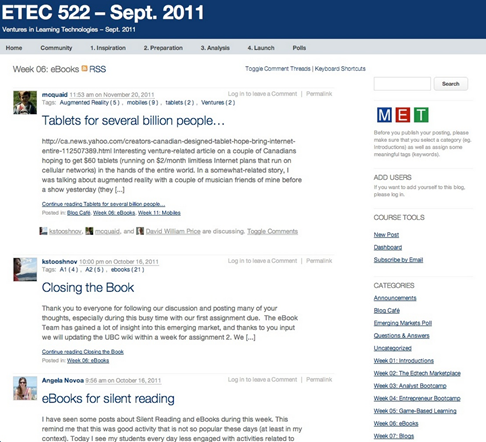

Where open educational resources are particularly valuable are in their use as interactive simulations, animations or videos that would be difficult or too expensive for an individual instructor to develop. Examples of simulations in science subjects such as biology and physics can be found here: PhET, or at the Khan Academy for mathematics, but there are many other sources as well.

But as well as open resources designated as ‘educational’, there is a great deal of ‘raw’ content on the Internet that can be invaluable for teaching. The main question is whether you as the instructor need to find such material, or whether it would be better to get students to search, find, select, analyze, evaluate and apply information. After all, these are key skills for a digital age that students need to have.

Certainly, at k-12, two-year college or undergraduate level, most content is not unique or original. Most of the time we are standing on the shoulders of giants, that is, organizing and managing knowledge already discovered. Only in the areas where you have unique, original research that is not yet published, or where you have your own ‘spin’ on content, is it really necessary to create ‘content’ from scratch. Unfortunately, though, it can still be difficult to find exactly the material you want, at least in a form that would be appropriate for your students. In such cases, then it will be necessary to develop your own materials, and this is discussed further in Step 7. However, building a course around already existing materials will make a lot of sense in many contexts.

You have a choice of focusing on content development or on facilitating learning. As time goes on, more and more of the content within your courses will be freely available from other sources over the Internet. This is an opportunity to focus on what students need to know, and on how they can find, evaluate and apply it. These are skills that will continue well beyond the memorisation of content that students gain from a particular course. So it is important to focus just as much on student activities, what they need to do, as on creating original content for our courses. This is discussed in more detail in Steps 6, 7 and 8.

So a critical step before even beginning to teach a course is look around and see what’s available and how this could potentially be used in the course or program you are planning to teach.

8. Step Five: Master the Technology

Taking the time to be properly trained in how to use standard learning technologies will in the long run save you a good deal of time and will enable you to achieve a much wider range of educational goals than you would otherwise have imagined.

8.1. The Exponential Growth in Learning Technologies

There are now many common technologies available for educational use:

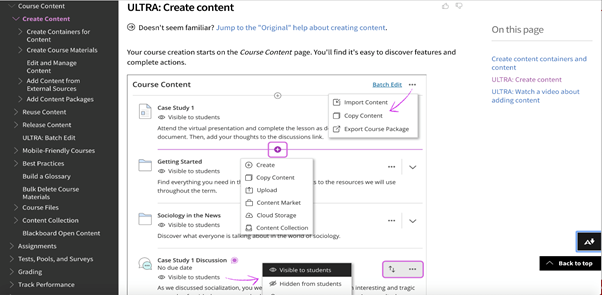

- Learning managements systems (such as Blackboard Learn, Moodle, D2L, Instructure/Canvas)

- Synchronous technologies (such as Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect, Big Blue Button, ZOOM, GoToMeeting, Microsoft Teams)

- Lecture recording technologies (such as GarageBand or Audacity for podcasts and Echo360 for lecture capture)

- Tablets and mobile devices, such as iPads, mobile phones, and the apps that run on them

- MOOCs and their many variants (SPOCs, TOOCs, etc.)

- other social media, including blogging software such as WordPress, wikis such as MediaWiki, Google Hangouts, Google Docs, and Twitter

- Learner-generated tools, such as e-portfolios (for example, Mahara)

- Search engines and translation tools, such as Google Search and Google Translate

It is not necessary to use all or any of these tools, but if you do decide to use them, you need to know not only how to operate such such technologies well, but also their pedagogical strengths and weaknesses. Although the technologies listed above will change over time, the general principles discussed in this section will continue to apply to other new technologies as they become available.

8.2. Use the Existing Institutional Technology

If your institution already has a learning management system such as Blackboard Learn, Moodle, Instructure or D2L, use it. Don’t get drawn into arguments about whether or not it is the best tool. Frankly, in functional terms, there are few important differences between the main LMSs. You may prefer the interface of one rather than another, but this will be more than overwhelmed by the amount of effort trying to use a system not supported by your institution. LMSs are not perfect but they have evolved over the last 20 years and in general are relatively easy to use, both by you and more importantly by the students. They provide a useful framework for organizing your online teaching, and if the LMS is properly supported you can get help when needed. There is enough flexibility in a learning management system to allow you to teach in a variety of different ways. In particular, take the time to be properly trained in how to use the LMS. A couple of hours of training can save you many hours in trying to get it to work the way you want.

A more important question to consider is whether you need to use an LMS at all – but that question should only be considered if the institution is willing to support alternatives, such as WordPress or Google Docs, otherwise you could end up spending too much time dealing with pure technology issues.

The same applies to synchronous web technologies such as Blackboard Collaborate, Adobe Connect, Big Blue Button or ZOOM. I have my preferences but they all do more or less the same thing. The differences in technology are nothing compared with the different ways in which you can use these tools. These are pedagogical or teaching decisions. Focus on these rather than finding the perfect technology.

Indeed, think carefully about when it would be best to use synchronous rather than asynchronous online tools. Synchronous tools are useful when you want to get a group of students together at one time, but such synchronous tools tend to be instructor-dominated (delivering lectures and controlling the discussion) and require students to be available at a set time. However, you could encourage students working in small teams on a project to use Collaborate or another synchronous tool such as ZOOM, which allows for setting up small sub-groups, to decide roles, discuss a topic and form a group view, or to finalize a project assignment, for instance. On the other hand, asynchronous tools such as an LMS provide learners with more flexibility than synchronous tools, and enable them to work more independently (an important skill for students to develop). And of course both synchronous and asynchronous tools can be used in conjunction, but that requires working out what each is best for.

8.3. Deceptively Easy Technology

Most of these technologies are deceptively easy to use, in the sense of getting started. They have been designed so that anyone without a computer science background can use them. However, over time they tend to become more sophisticated with a wide range of different functions. You won’t need to use all the functions, but it will help if you are aware that they exist, and what they can and can’t do. If you do want to use a particular feature, it is best to get training so that you can use it quickly and effectively.

8.4. Keep Current, As Far As Possible

New technologies keep arriving all the time. It is best to focus on new tools that seem functionally different from existing tools, rather than trying to check every new synchronous meeting system, for instance. It is too difficult for any single teacher or instructor to keep up to date with newly emerging technologies and their possible relevance for teaching. This is really the job of any well-run learning technology support unit. So make the effort to attend a once-a-year briefing on new technologies, then follow-up with a further session on any tool that might be of interest.

This kind of briefing and training should be provided by the centre or unit that provides learning technology support. If your institution does not have such a unit, or such training, think very carefully about whether to use technology extensively in your teaching – even teachers and instructors with a lot of experience in using technology for teaching need such support.

Furthermore, new functions are constantly being added to existing tools. For instance, if you are using Moodle, there are ‘plug-ins’ (such as Mahara) that allow students to create and manage their own e-portfolios or electronic records of their work. Learning analytics software for LMSs, which allow you to analyze the way students are using the LMS and how this relates to their performance, is another recent wave of plug-ins.

Thus a session spent learning the various features of your learning management system and how best to use them will be well worthwhile, even if you have been using it for some time, but didn’t have a full training on the system. Particularly important is knowing how to integrate different technologies, such as online videos within an LMS, so that the technology appears seamless to students.

Lastly, don’t get locked into using only your favourite technology, and keeping a closed mind against anything else. It is is a natural tendency to try to protect the use of a technology that has taken a good deal of time and effort to master, especially if it has served you and your students well in the past, and new technology is not necessarily better for teaching than old technology. Nevertheless, game-changers do come along occasionally, and may well have educational benefits that were not previously considered. One tool is unlikely to do everything you need as a teacher; a well-chosen mix of tools is likely to be more effective. Keep an open mind and be prepared to make a shift if necessary.

8.5. Relate Your Technology Training to How You Want to Teach

There are really two distinct but strongly related components of using technology:

- How the technology works

- What it should be used for

These are tools built to assist you, so you have to be clear as to what you are trying to achieve with the tools. This is an instructional or pedagogical issue. Thus if you want to find ways to engage students, or to give them practice in developing skills, such as solving quadratic equations, learn what the strengths or weaknesses are of the various technologies.

This is somewhat of an iterative process. When a new tool or a new feature is being described or demonstrated, think of how this might fit with or facilitate one of your teaching goals. But also be open to possibly changing your goals or methods to take advantage of a tool in enabling you to do something you had not thought of doing before. For example, an e-portfolio plug-in might lead you to change the way you assess students, so that learning outcomes are more ‘authentic’ and evidence-based than say with a written essay. (This will be discussed further in the next step ‘Setting appropriate goals for learning.’)

Avoid Duplicating Your Classroom TeachingPodcasts and lecture capture enable lectures to be recorded, stored and downloaded by students. So why bother to learn how to use other online technologies such as an LMS? evidence-based research on the limitations of lectures was discussed. In brief, students in general don’t learn well online using recordings of ‘transmissive’ classroom lectures. Perhaps of equal importance, you are likely to end up doing more work because you are likely to be inundated with individual e-mails asking for clarification, or have a very high student failure rate, if you do not adapt the lecture to the online learning environment.

This is not to say that the occasional recording from you as the instructor would not be valuable. However, it is best to keep it to 10-15 minutes maximum, and it should add something unique to the course, such as being about your own research, or a guest professor being interviewed, or your relating a news item to issues or principles being studied in the course. It may even be better as an audio-only podcast, so students can concentrate on the words and possibly relate them to other learning materials, such as diagrams, graphics or animations on a web site.

If you must use lecture capture, think about structuring your in-class lecture so that it can be edited into separate sections of say 10-15 minutes. One way of doing this is pausing at an appropriate point to ask for questions from the classroom students, thus providing a clear ‘editing’ point for the video version. Then provide online work to follow up each of the recorded components, such as a topic for discussion on an online forum, some online student research or further reading on the topic.

However, in general, delivery of content is much better done through a learning management system, where it is permanent, organized and structured (see Step 7 later), available in discrete amounts, can be accessed at any time, and can be repeated as often as is needed by the learner. Or it may be even better to get students to find, analyse and organise content for themselves, in which case you may need tools other than an LMS, such as blog software such as WordPress, an e-portfolio or wiki. Again, the decision should be driven by pedagogical thinking, rather than trying to make one tool fit every circumstance.

8.6. Benefits of Mastering the Technology

Online learning technologies such as learning management systems have been designed to fit the online learning environment. This requires some adjustment and learning on the part of teachers and instructors whose primary experience is in classroom teaching.

Like any tool, the more you know about it the better you are likely to use it. Thus formal training on the technology is necessary but need not be onerous. Usually a total of two hours specific and well organized instruction should be sufficient on how to use any particular tool, such as a learning management or lecture capture system, e-portfolio or synchronous webinar tool, with a one hour review session every year.

9. Step Six: Set Appropriate Learning Goals

9.1. Setting Goals for Learning in a Digital Age

In many school systems, curriculum and learning goals are already pre-determined by national, state or provincial curriculum committees and/or ministries of education. In many trades and vocational areas, industry training boards or employers’ associations set learning goals or desired outcomes or competencies that need to be followed for qualifications to be accredited. Even in a university, an instructor (particularly a contract instructor or adjunct) may ‘inherit’ a course where the goals are already set, either by a previous instructor or by the academic department.

Nevertheless, there remain many contexts where teachers and instructors have a degree of control over the goals of a particular course or program. In particular, a new course or program – such as an online masters program aimed at working professionals – offers an opportunity to reconsider desired learning outcomes and goals. Especially where curriculum is framed mainly in terms of content to be covered rather than by skills to be developed, there may still be room for manoeuvre in setting learning goals that would also include, for instance, intellectual skills development. In other contexts, the development or focus may be on more affective skills, such as sympathy or empathy, or on the development of manual or operational skills.

9.2. Learning Goals for a Digital Age

I listed a number of skills that learners will need in a digital age, including:

- Modern communication skills

- Independent learning

- Ethics and responsibility

- Teamwork and flexibility

- Thinking skills including:

- Critical thinking

- Problem solving

- Creative thinking

- Strategizing and planning

- Digital skills

- Knowledge management

These are examples of the kinds of goal that need to be identified. More traditional goals might also be included, such as comprehension and application of specific areas of content. These goals or outcomes might be expressed in terms of Bloom’s taxonomy (1956) or the Royal Bank of Canada’s (2018) or in a variety of other ways. All these skills need to be embedded or built within the needs of a specific subject domain. In other words, they are skills that need to be specific to a subject area rather than general. At the same time, students who develop such skills within any particular subject area will be better prepared for a digital age.

Your list of goals for a course may – indeed, should be – different from mine, but it will be essential to do the kind of analysis recommended in Step 1 (deciding how you want to teach), and then to decide on what the learning goals should be, based on:

- Your understanding of the needs of the student

- The needs of the subject domain

- The demands of the external world

I have placed a particular emphasis on the development of intellectual skills. As with all learning goals, the teaching needs to be designed in such a way that students have opportunities to learn and practice such skills, and in particular, such skills need to be evaluated as part of the formal assessment process. Perhaps more challenging is to identify what you will be adding to general skills development such as critical thinking. What is the level of critical thinking skills that students will come with, and how do I make sure they progress in their ability in this skill during the course? This emphasises the value of having learning outcomes clearly identified for a whole program, perhaps using a curriculum mapping tool such as Daedalus.

What this means in terms of course design is using the Internet increasingly as a major resource for learning, giving students more responsibility for finding and evaluating information themselves, and instructors providing criteria and guidelines for finding, evaluating, analysing and applying information within a specific knowledge domain. This will require a critical approach to online searches, online data, news or knowledge generation in specific knowledge domains – in other words the development of critical thinking about the Internet and modern media – both their potential and limitations within a specific subject domain.

9.3. Bring in the Outside World

One great characteristic of modern media is the opportunity to bring in the world to your teaching in many ways, for instance:

- By directing students to online sites, and encouraging them to identify and share relevant sites.

- Students themselves can collect data or provide real world examples of concepts or issues covered in the course, through the use of cameras in mobile phones, or audio interviews of local experts, or identifying relevant open educational resources.

- Setting up a course wiki that both you and the students contribute to, and make it open to other professors and students to contribute to, depending on the topic.

- If you are teaching professional masters or diploma programs, or MOOCs, the students themselves will have very relevant world experiences that can be drawn into the program. This is a great way to enable students to evaluate and apply knowledge within their subject domain.

There are many other possible goals that are either impossible to meet without using the Internet, or would be very difficult to do in a purely classroom environment. The art of the instructor is to decide which are relevant, and which in particular could be key learning goals for the course.

9.4. Learning Goals: The Same or Different, Depending on Mode of Delivery?

In many cases, it will be appropriate (indeed, essential) to keep the same teaching goals for an online course as in a similar face-to-face course. Many dual-mode institutions, campus-based institutions who also offer credit courses online, such as the University of British Columbia, Penn State, University of Nebraska, offer the same courses both face-to-face and online, particularly in the fourth year of an undergraduate program. Usually the transcript of the exam grade makes no distinction as to whether the course was done online or face-to-face, since the students take the same end of course exam, and the actual content covered is usually identical in each version.

Nevertheless, there may be occasions where some goals in the campus-based class may need to be sacrificed for different but equally valuable goals that can be achieved better online. It is also important to remember that although it may be possible to achieve the same goals online as in class, the design of the teaching will likely have to be different in the online environment. Thus often the goals remain the same, but the method changes. This will be discussed further in Steps 7 and 8. The important point is to be aware that some things can be more easily done in a campus environment, and others better done online, then to build your teaching around these somewhat different goals. Using a blended approach may enable you to widen the range of goals, but be careful not to overload students by doing this.

9.5. Assessment is the Key

It is pointless to introduce new learning goals or outcomes then not assess how well students have achieved those goals. Assessment drives student behaviour. If they are not to be assessed on the skills outlined above, they won’t make the effort to develop them. The main challenge may not be in setting appropriate goals for online learning, but ensuring that you have the tools and means to assess whether students have achieved those goals.

And even more importantly, it is necessary to communicate very clearly to students these new learning goals and how they will be assessed. This may come as a shock to many students who are used to being fed content then tested on their memory of it.

In some ways, with the Internet (as with other media), the medium is the message. Knowledge is not completely neutral. What we know and how we know it are affected by the medium through which we acquire knowledge. Each medium brings another way of knowing. We can either fight the medium, and try to force old content into new bottles, or we can shape the content to the form of the medium. Because the Internet is such a large force in our lives, we need to be sure that we are making the most of its potential in our teaching, even if that means changing somewhat what and how we teach. If we do that, our students are much more likely to be better prepared for a digital age.10. Step Seven: Design Course Structure and Learning Activities

The importance of providing students with a structure for learning and setting appropriate learning activities is probably the most important of all the steps towards quality teaching and learning, and yet the least discussed in the literature on quality assurance.

10.1. Some General Observations About Structure in Teaching

First a definition, since this is a topic that is rarely directly discussed in either face-to-face or online teaching, despite structure being one of the main factors that influences learner success. Three dictionary definitions of structure are as follows:

- Something made up of a number of parts that are held or put together in a particular way.

- The way in which parts are arranged or put together to form a whole

- The interrelation or arrangement of parts in a complex entity

Teaching structure would include two critical and related elements:

- The choice, breakdown and sequencing of the curriculum (content)

- The deliberate organization of student activities by teacher or instructor (skills development; and assessment)

This means that in a strong teaching structure, students know exactly what they need to learn, what they are supposed to do to learn this, and when and where they are supposed to do it. In a loose structure, student activity is more open and less controlled by the teacher (although a student may independently decide to impose his or her own ‘strong’ structure on their learning). The choice of teaching structure of course has implications for the work of teachers and instructors as well as students.

In terms of the definition, ‘strong’ teaching structure is not inherently better than a ‘loose’ structure, nor inherently associated with either face-to-face or online teaching. The choice (as so often in teaching) will depend on the specific circumstances. However, choosing the optimum or most appropriate teaching structure is critical for quality teaching and learning, and while the optimum structures for online teaching share many common features with face-to-face teaching, in other ways they differ considerably.

The three main determinants of teaching structure are:

(a) the organizational requirements of the institution

(b) the preferred philosophy of teaching of the instructor

(c) the instructor’s perception of the needs of the students

10.2. Institutional Organizational Requirements of Face-to-Face Teaching

Although the institutional structure in face-to-face teaching is so familiar that it is often unnoticed or taken for granted, institutional requirements are in fact a major determinant of the way teaching is structured, as well as influencing both the work of teachers and the life of students. I list below some of the institutional requirements that influence the structure of face-to-face teaching in post-secondary education:

- The minimum number of years of study required for a degree

- The program approval and review process

- The number of credits required for a degree

- The relationship between credits and contact time in the class

- The length of a semester and its relationship to credit hours

- Instructor:student ratios

- The availability of classroom or laboratory spaces

- Time and location of examinations

There are probably many more. There are similar institutional organizational requirements in the school system, including the length of the school day, the timing of holidays, and so on. (To understand the somewhat bizarre reasons why the Carnegie Unit based on a Student Study Hour came to be adopted in the USA, see Wikipedia.)

As our campus-based institutions have increased in size, so have the institutional organizational requirements ‘solidified’. Without this structure it would become even more difficult to deliver consistent teaching services across the institution. Also such organizational consistency across institutions is necessary for purposes of accountability, accreditation, government funding, credit transfer, admission to graduate school, and a host of other reasons. Thus there are strong systemic reasons why these organizational requirements of face-to-face teaching are difficult if not impossible to change, at least at the institutional level.

Thus any teacher is faced by a number of massive constraints. In particular, the curriculum needs to fit within the time ‘units’ available, such as the length of the semester and the number of credits and contact hours for a particular course. The teaching has to take into account class size and classroom availability. Students (and teachers and instructors) have to be at specific places (classrooms, examination rooms, laboratories) at specific times.

Thus despite the concept of academic freedom, the structure of face-to-face teaching is to a large extent almost predetermined by institutional and organizational requirements. I am tempted to digress to question the suitability of such structural limitations for the needs of learners in a digital age, or to wonder whether faculty unions would accept such restrictions on academic freedom if they did not already exist, but the aim here is to identify which of these organizational constraints apply also to online learning, and which do not, because this will influence how we can structure teaching activities.

10.3. Institutional Organizational Requirements of Online Teaching

One obvious challenge for online learning, at least in its earliest days, was acceptance. There was (and still is) a lot of skepticism about the quality and effectiveness of online learning, especially from those that have never studied or taught online. So initially a lot of effort went into designing online learning with the same goals and structures as face-to-face teaching, to demonstrate that online teaching was ‘as good as’ face-to-face teaching (which, research suggests, it is).

However, this meant accepting the same course, credit and semester assumptions of face-to-face teaching. It should be noted though that as far back as 1971, the UK Open University opted for a degree program structure that was roughly equivalent in total study time to a regular, campus-based degree program, but which was nevertheless structured very differently, for instance, with full credit courses of 32 weeks’ study and half credit courses of 16 weeks’ study. One reason was to enable integrated, multi-disciplinary foundation courses. The Western Governors’ University, with its emphasis on competency-based learning, and Empire State College in New York State, with its emphasis on learning contracts for adult learners, are other examples of institutions that have different structures for teaching from the norm.

If online learning programs aim to be at least equivalent to face-to-face programs, then they are likely to adopt at least the minimum length of study for a program (e.g. four years for a bachelor’s degree in North America), the same number of total credits for a degree, and hence implicit in this is the same amount of study time as for face-to-face programs. Where the same structure begins to break down though is in calculating ‘contact time’, which by definition is usually the number of hours of classroom instruction. Thus a 13 week, 3 credit course is roughly equal to three hours a week of classroom time over one semester of 13 weeks.

There are lots of problems with this concept of ‘contact hours’, which nevertheless is the standard measuring unit for face-to-face teaching. Study at a post-secondary level, and particularly in universities, requires much more than just turning up to lectures. A common estimate is that for every hour of classroom time, students spend a minimum of another two hours on readings, assignments, etc. Contact hours vary enormously between disciplines, with usually arts/humanities having far less contact hours than engineering or science students, who spend a much larger proportion of time in labs. Another limitation of ‘contact hours’ is that it measures input, not output.

When we move to blended or hybrid learning, we may retain the same semester structure, but the ‘contact hour’ model starts to break down. Students may spend the equivalent of only one hour a week in class, and the rest online – or maybe 15 hours in labs one week, and none the rest of the semester.

A better principle would be to ensure that the students in blended, hybrid or fully online courses or programs work to the same academic standards as the face-to-face students, or rather, spend the equivalent ‘notional’ time on doing a course or getting a degree. This means structuring the courses or programs in such a way that students have the equivalent amount of work to do, whether it is online, blended or face-to-face. However, the way that work will be distributed can very considerably, depending on the mode of delivery.

10.4. How Much Work is an Online Course?

Before decisions can be made about the best way to structure a blended or an online course, some assumption needs to be made about how much time students should expect to study on the course. We have seen that this really needs to be equivalent to what a full-time student would study. However, just taking the equivalent number of contact hours for the face-to-face version doesn’t allow for all the other time face-to-face students spend studying.

A reasonable estimate is that a three credit undergraduate course is roughly equivalent to about 8-9 hours study a week, or a total of roughly 100 hours over 13 weeks. (A full-time student then taking 10 x 3 credits a year, with five 3 credit courses per semester, would be studying between 40-45 hours a week during the two semesters, or slightly less if the studying continued over the inter-semester period.).

Now this is my guideline. You don’t have to agree with it. You may think this is too much or too little for your subject. That doesn’t matter. You decide the time. The important point though is that you have a fairly specific target of total time that should be spent on a course or program by an average student, knowing that some will reach the same standard more quickly and others more slowly. This total student study time for a particular chunk of study such as a course or program provides a limit or constraint within which you must structure the learning. It is also a good idea to make it clear to students from the start how much time each week you are expecting them to work on the course.

Since there is far more content that could be put in a course than students will have time to study, this usually means choosing the minimum amount of content for the course for it to be academically sound, while still allowing students time for activities such as individual research, assignments or project work. In general, because instructors are experts in a subject and students are not, there is a tendency for instructors to underestimate the amount of work required by a student to cover a topic. Again, an instructional designer can be useful here, providing a second opinion on student workload.

10.5. Strong or Loose Structure?

Another critical decision is just how much you should structure the course for the students. This will depend partly on your preferred teaching philosophy and partly on the needs of the students.

If you have a strong view of the content that must be covered in a particular course, and the sequence in which it must be presented (or if you are given a mandated curriculum by an accrediting body), then you are likely to want to provide a very strong structure, with specific topics assigned for study at particular points in the course, with student work or activities tightly linked.

If on the other hand you believe it is part of the student’s responsibility to manage and organize their study, or if you want to give students some choice about what they study and the order in which they do it, so long as they meet the learning goals for the course, then you are likely to opt for a loose structure.

This decision should also be influenced by the type of students you are teaching. If students come without independent learning skills, or know nothing about the subject area, they will need a strong structure to guide their studies, at least initially. If on the other hand they are fourth year undergraduates or graduate students with a high degree of self-management, then a looser structure may be more suitable to their needs. Another determining factor will be the number of students in your class. With large numbers of students, a strong, well defined structure will be necessary to control your workload, as loose structures require more negotiation and support for individual students.

My preference is for a strong structure for fully online teaching, so students are clear about what they are expected to do, and when it has to be done by, even at graduate level. The difference is that with post-graduates, I will give them more choices of what to study, and longer periods to complete more complex assignments, but I will still define clearly the desired learning outcomes in terms of skill development in particular, such as research skills or analytical thinking, and provide clear deadlines for student work, otherwise I find my workload increases dramatically.

ETEC 522 at the University of British Columbia is a loosely structured graduate course, in that students organize their own work around the course themes. The course design changes every year because the course deals with a fast-changing study domain (the potential of new technologies for education), an example of agile design.

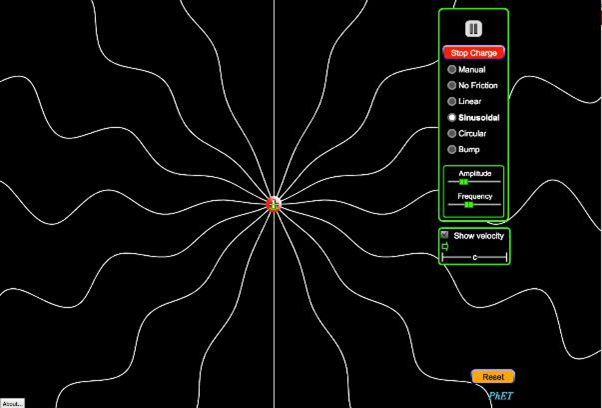

The web page illustrated in Figure 7 though from the 2011 version of the course demonstrates clearly a relatively loose structure. The weekly topic structure is on the right, covering seven weeks of the course, the remaining six being time for students to work on their projects. The outcomes of student activities are in the main body, posted by students through their blogs. Note this is not using a learning management system, but WordPress, a content management system, which allows students more easily to post and organize their activities.

Blended learning provides an opportunity to enable students to gradually take more responsibility for their learning, but within a ‘safe’ structure of a regularly scheduled classroom event, where they have to report on any work they have been required to do on their own or in small groups. This means thinking not just at a course level but at a program level, especially for undergraduate programs. A good strategy would be to put a heavy emphasis on face-to-face teaching in the first year, and gradually introduce online learning through blended or hybrid classes in second and third year, with some fully online courses in the fourth year, thus preparing students better for lifelong learning.

10.6. Moving a Face-to-Face Course Online